The Arbiter of All Culture

What the world needs now is Edmund Wilson. There is no cultural criticism, no literary criticism, no historical perspective, at least not in the sense that Wilson created it in his volumes of essays, and in journals like Vanity Fair, The New Republic, The New Yorker, and The New York Review of Books.

Wilson came into the world in Red Bank, New Jersey on May 8, 1895. He attended The Hill School, an eastern boarding academy located in Pennsylvania that prepared students for college. His literary aspirations began there when he edited the school’s magazine, The Record. He went on to Princeton University and started on his journalism career at the New York Sun after graduating. Rene Wellek, writing in Comparative Literature Studies (Volume 15, No. 1), says Wilson “disclaimed being a literary critic.” He quotes Wilson in 1959: “I think of myself simply as a writer and a journalist. I am as much interested in history as I am in literature.”

The journalist Wilson came to Vanity Fair as the managing editor, He later joined the staff of many other cultural publications that are icons in American cultural literature. These articles, essays, and pieces were later collected into a number of important books, including Axel’s Castle: A Study in the Imaginative Literature of 1870-1930, The Shores of Light: A Literary Chronicle of the Twenties and Thirties, The Triple Thinkers: Ten Essays on Literature , and The Wound and the Bow: Seven Studies in Literature. His most famous book is probably To The Finland Station: A Study in the Writing and Acting of History, a chronicle of Marxism and the rise of socialism in the twentieth century. Many of Wilson’s best pieces take on the influence of Marx and Freud, and he applies their philosophies to the analysis of literature and history. In a nation that found itself locked in a Cold War with the Soviet Union, this was daring stuff. And Wilson was not afraid of changing his mind. He later moved away from his admiration of communism, becoming shocked and disillusioned with the Soviet purges.

Wilson could be polemical and cantankerous, but his point of view came from a place of deep thought and consideration. He was willing to step out in front of American life and thought and take a critical stand. For his courage, he inspired generations of literary and cultural criticism.

My favorite of Wilson’s books is A Piece of My Mind: Reflections at Sixty. Here is Wilson in all his difficult and demanding glory. Here to, is Wilson at his most poignant. This is a man who refused to pay income tax as a protest against America’s Cold War policies. This is a man who supported communism when all of America was caught up in the witch hunts of the HUAC hearings. By the age of sixty, Wilson had adopted unpopular opinions, and later modified and even refuted them publicly. Upon reflection, Wilson wrote, “And am I, too, I wonder, stranded? Am I, too, an exceptional case? When, for example, I look through Life magazine, I feel that I do not belong to the country depicted there, that I do not even live in that country. Am I, then, in a pocket of the past?”

Wilson died in 1972, but I would argue that far from residing in a “pocket of the past,” we need writers, critics, and yes, journalists like him now. Unfortunately, arbiters of culture and literature like Alfred Kazin, Frank Kermode, Norman Podhoretz, Susan Sontag, and indeed, Edmund Wilson, are voices all but ignored in today’s world. We need to listen to them again, and to encourage new writers to pick up the mantle and carry the torch. We require a more intelligent America, and it is a sad day when no one is there to make us think for ourselves. It is a world of greater complexity and lesser minds, leaving us alone in the woods without a match to light the way home.

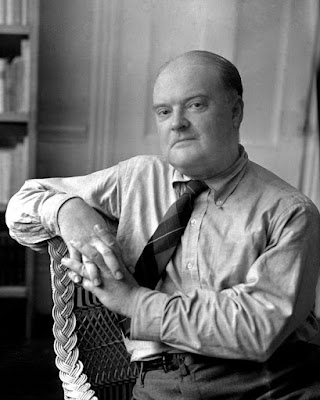

Photo: © Bettman/CORBIS

Comments

Post a Comment