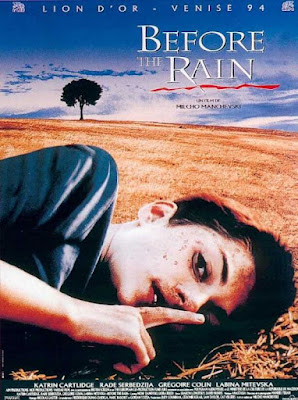

Before The Rain

Before The Rain (Macedonia, 1994)

Dir. Milcho Mancevski

Criterion; $39.95, DVD

Milcho Mancevski’s Before The Rain, utilizes a circular narrative to uniquely portray the civil strife in Macedonia between the Orthodox Christians and the Muslim Albanians in the 1980s and 1990s. The film is beautifully shot, with a film clarity that appears almost of digital quality, highlighting the rugged and sparse terrain of the Macedonian countryside. The theme, expressed by one of the characters, that “Time never dies. The circle is not round,” recurs frequently in the fragmented story line.

Using the motif of tomatoes on the vine, we see a young priest who has taken a vow of silence, picking the fruit in the crystal clear Macedonian sun. This section of the film is entitled, Words, and adds the additional motif of almost the complete absence of words, or in limited occasion, the inability of words to express thoughts and emotions.

The priest, upon returning to his Spartan cell, discovers a young androgynous figure hiding in his bed. The young person is a girl who is hiding from a mob bent on exacting revenge upon her for murdering one of their members. The young priest is startled by her appearance, and runs from the cell to seek help from an elderly priest. Since he is unable to speak, the elder believes he wants company to go into the night to urinate before bed. Because of this misunderstanding, the young priest returns to his cell and allows the girl to sleep on the floor. She also eats some of the tomatoes, representing the extreme poverty and starvation of the ethnic Albanians. The mob storms the monastery and conducts a search, but somehow, the girl avoids detection. The mob displays particular cruelty, with one member callously shooting a cat several times. Mancevski uses these visual cues to portray the violence and brutality of the ethnic and religious conflict.

The priest is forced to resign and flee the monastery with the young girl as the segment ends. Upon leaving, they pass a funeral, and a woman who cries out upon witnessing the burial. Later, the priest is captured by members of the girl’s family who wish to punish the girl for her actions. In the melee, she is shot and killed by her own brother, and dies face down on the earth with the priest tearfully crouching next to her.

The second segment, entitled Faces, jumps to London where a young magazine editor finds herself torn between her husband and a former lover, a photographer who has been covering wars and violence throughout the world. He is world weary and haggard, even as the husband is neatly groomed and a business man. The woman rejects overtures from her former lover and after a sexual encounter in the back of a taxi, leaves him to go to her husband. She meets him in a restaurant where a bloody tragedy occurs. A bearded and swarthy man, not unlike the Orthodox Christians and Albanians in the first segment, causes a disruption in the restaurant, is expelled, and later returns with a gun. He fires indiscriminately into the restaurant, killing many people, including the husband.

Mancevski makes clear in Faces that ethnic strife and violence do not respect borders. Was the shooter a Christian or an Albanian? We do not know for certain, but he is ethnic, gesticulating wildly in his conflict with the restaurant employees, and babbling in a strange tongue. He is quick-tempered, uncouth and violent, contrasting sharply with the husband who is urbane and civil. The Londoners are not spared the violence even in a sharply ordered, civilized city.

The kick in this section is in the photographs that that editor works with at her office. They are of the young girl’s murder from Words. It is a bit disconcerting, yet deeply involving, that the time line is unclear. This again reinforces the theme of “the circle is not round.”

The final section, Pictures, depicts the photographer from Faces returning to his home village, a place he has not visited in some time. After inadvertently causing another man’s death, he is tired of being caught up in war as a journalist, and longs to rediscover a place where he belongs. A woman he once loved, Hana, is now a widow, and asks him to help her with her daughter, the young girl from Words. The photographer’s fate is not to escape the violence he has seen, and in his desire to help the young girl, he becomes a victim of the that same violence. His fate leads us back to the first segment and the funeral we witness in passing.

Mancevski is clever with his fragmented time line in the film. He illustrates that violence carries over, through time and space, never ending, and always a threat, in cities and in rural areas. No one is safe, and the threat never ends. It is somewhat pessimistic to think that human beings will never escape their need to shed blood over religion and ethnicity, but the film maker’s thesis can hardly be refuted by history.

To add gravitas and epic scope to his story, Mancevski weaves in subtle lines from Shakespeare. He alludes to Romeo and Juliet when a character advises another to “Deny thy father and refuse thy name.” It is not a simple matter to deny personal history, ethnicity, or religion. Are these things not the causes of all wars and violence? Another character, upon realizing he has inadvertently caused more bloodshed, says, “Will these hands never be clean?” an echo of the famous lines in Macbeth when the murderous Thane asks the heavens if he will ever be free of culpability in the rivers of blood that run through that play. It is an effective conceit that adds much to the scope and heft of the narrative of the film.

Before The Rain is a stunningly realized piece of historical narrative. The gathering storm clouds that hiss lightening and rumble ominously throughout the film, especially during the bloody climax of the final segment, add sonic and visual punctuation, lending the work its title. Mancevski’s masterpiece is emotional and intense, possibly lacking the distance of years to mature the narrative, but one can feel both the violence and the endless cycle of brutality so heavy a burden on the shoulders of all humanity with roots in the fertile soil of bigotry, religious persecution, and ethnic cleansing.

Dir. Milcho Mancevski

Criterion; $39.95, DVD

Milcho Mancevski’s Before The Rain, utilizes a circular narrative to uniquely portray the civil strife in Macedonia between the Orthodox Christians and the Muslim Albanians in the 1980s and 1990s. The film is beautifully shot, with a film clarity that appears almost of digital quality, highlighting the rugged and sparse terrain of the Macedonian countryside. The theme, expressed by one of the characters, that “Time never dies. The circle is not round,” recurs frequently in the fragmented story line.

Using the motif of tomatoes on the vine, we see a young priest who has taken a vow of silence, picking the fruit in the crystal clear Macedonian sun. This section of the film is entitled, Words, and adds the additional motif of almost the complete absence of words, or in limited occasion, the inability of words to express thoughts and emotions.

The priest, upon returning to his Spartan cell, discovers a young androgynous figure hiding in his bed. The young person is a girl who is hiding from a mob bent on exacting revenge upon her for murdering one of their members. The young priest is startled by her appearance, and runs from the cell to seek help from an elderly priest. Since he is unable to speak, the elder believes he wants company to go into the night to urinate before bed. Because of this misunderstanding, the young priest returns to his cell and allows the girl to sleep on the floor. She also eats some of the tomatoes, representing the extreme poverty and starvation of the ethnic Albanians. The mob storms the monastery and conducts a search, but somehow, the girl avoids detection. The mob displays particular cruelty, with one member callously shooting a cat several times. Mancevski uses these visual cues to portray the violence and brutality of the ethnic and religious conflict.

The priest is forced to resign and flee the monastery with the young girl as the segment ends. Upon leaving, they pass a funeral, and a woman who cries out upon witnessing the burial. Later, the priest is captured by members of the girl’s family who wish to punish the girl for her actions. In the melee, she is shot and killed by her own brother, and dies face down on the earth with the priest tearfully crouching next to her.

The second segment, entitled Faces, jumps to London where a young magazine editor finds herself torn between her husband and a former lover, a photographer who has been covering wars and violence throughout the world. He is world weary and haggard, even as the husband is neatly groomed and a business man. The woman rejects overtures from her former lover and after a sexual encounter in the back of a taxi, leaves him to go to her husband. She meets him in a restaurant where a bloody tragedy occurs. A bearded and swarthy man, not unlike the Orthodox Christians and Albanians in the first segment, causes a disruption in the restaurant, is expelled, and later returns with a gun. He fires indiscriminately into the restaurant, killing many people, including the husband.

Mancevski makes clear in Faces that ethnic strife and violence do not respect borders. Was the shooter a Christian or an Albanian? We do not know for certain, but he is ethnic, gesticulating wildly in his conflict with the restaurant employees, and babbling in a strange tongue. He is quick-tempered, uncouth and violent, contrasting sharply with the husband who is urbane and civil. The Londoners are not spared the violence even in a sharply ordered, civilized city.

The kick in this section is in the photographs that that editor works with at her office. They are of the young girl’s murder from Words. It is a bit disconcerting, yet deeply involving, that the time line is unclear. This again reinforces the theme of “the circle is not round.”

The final section, Pictures, depicts the photographer from Faces returning to his home village, a place he has not visited in some time. After inadvertently causing another man’s death, he is tired of being caught up in war as a journalist, and longs to rediscover a place where he belongs. A woman he once loved, Hana, is now a widow, and asks him to help her with her daughter, the young girl from Words. The photographer’s fate is not to escape the violence he has seen, and in his desire to help the young girl, he becomes a victim of the that same violence. His fate leads us back to the first segment and the funeral we witness in passing.

Mancevski is clever with his fragmented time line in the film. He illustrates that violence carries over, through time and space, never ending, and always a threat, in cities and in rural areas. No one is safe, and the threat never ends. It is somewhat pessimistic to think that human beings will never escape their need to shed blood over religion and ethnicity, but the film maker’s thesis can hardly be refuted by history.

To add gravitas and epic scope to his story, Mancevski weaves in subtle lines from Shakespeare. He alludes to Romeo and Juliet when a character advises another to “Deny thy father and refuse thy name.” It is not a simple matter to deny personal history, ethnicity, or religion. Are these things not the causes of all wars and violence? Another character, upon realizing he has inadvertently caused more bloodshed, says, “Will these hands never be clean?” an echo of the famous lines in Macbeth when the murderous Thane asks the heavens if he will ever be free of culpability in the rivers of blood that run through that play. It is an effective conceit that adds much to the scope and heft of the narrative of the film.

Before The Rain is a stunningly realized piece of historical narrative. The gathering storm clouds that hiss lightening and rumble ominously throughout the film, especially during the bloody climax of the final segment, add sonic and visual punctuation, lending the work its title. Mancevski’s masterpiece is emotional and intense, possibly lacking the distance of years to mature the narrative, but one can feel both the violence and the endless cycle of brutality so heavy a burden on the shoulders of all humanity with roots in the fertile soil of bigotry, religious persecution, and ethnic cleansing.

Comments

Post a Comment