A House of My Own

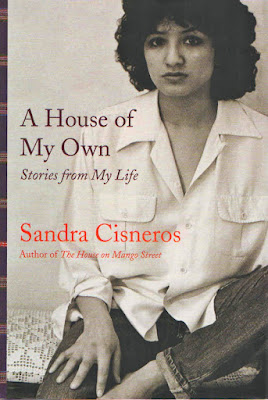

“I like to tell stories,” Sandra Cisneros writes at the end of her first novel, The House On Mango Street (Vintage, 1991). “I tell them inside my head…I make a story for my life, for each step my brown shoe takes. I say, ‘And so she trudged up the wooden stairs, her sad brown shoes taking her to the house she never liked.’” Over the years, Cisneros has found a few houses she has liked, in Greece, in Chicago, in San Antonio, and now in Mexico, as she reveals in her recent essay collection, A House of My Own (Knopf, 2015).

First, the book is gorgeously printed on rich, heavy paper. Yes, it makes the book weightier than a normal hardback, but it definitely elevates the art of the book as a thing of beauty. This is a book well-made, both in physical construction and in the literature it contains. The essays come from diverse publications across the years, from 1984 to 2014, as Cisneros documents her life as human being and artist. She has never been the shy, retiring type, and her voice is very strong in this collection. And that is what drew me to her work in the first place.

That being said, second, the essays here are a mixed bag: some are very strong in the tradition of her first novel, with clear voice tinged with a bit of sadness, maybe, but also with a lust for life and for being her own person. Others fall into reportage or recollection of an event in her time that resonates down through the years.

I first encountered Cisneros’ work as a teacher. I have used The House On Mango Street in many, many classes over the years. It is a book that transcends ethnicity and economic status; rich kids, poor kids, white, black or brown kids, all of them respond to the novel of vignettes and revel in Cisneros’ voice. That voice—filtered through diverse characters—is one to be savored, remembered and treasured.

I saw Cisneros speak at UCLA one year during an English teachers’ workshop. I normally am not moved by author readings. I like to hear the voice in my head as I read, and I find that even an author reading the work, and even more the movie version of a novel, to be distracting and not what I imagined the characters to be. Sandra Cisneros was different on that long ago Saturday. She read from her novel and did all the voices, and they were exactly as I heard them in my head when reading. She taught us how to introduce the cross-sensory teaching of writing that can be applied to poetry or prose. Take something that stereotypically is perceived through one sense and describe it using another sense. So one might say, “I could smell the rain in the trees.” The purpose is to jolt the reader out of the clichés we use to describe things: the sky was blue, the summer day was hot. Changing up the sensory description forces the reader to “revise” how they perceive the world. This works very well for all types of writing, even essays. It is living the advice Charles Dickens gave to writers: “Make me see.” It was a truly memorable workshop.

In this latest collection, Cisneros’ voice is older and wiser. She demonstrates her passion and character, tracing her growth as a human being and an artist. Some of the pieces began their lives as lectures or speeches. Others might be best described as travelogues or journal entries. Still others are introductions to other writers’ work. Long ago loves and important opportunities, both missed and taken, fall from the pages. She tells us of the important writers in her life—Marguerite Duras, Gwendolyn Brooks and Eduardo Galeano, to name a few—and the way art and culture influence her living and writing.

My favorite essay in the collection is the one she wrote for the 25th anniversary edition of The House On Mango Street. The piece centers on her mother and Cisneros’ own search for a home in the world. Her parents worry about her—not married, seemingly adrift, different than her own culture’s expectations to be somebody’s wife, somebody’s mother. The final image from the essay is of Cisneros and her mother on the roof of her writing studio in San Antonio watching the sun set. It is an intimate and gorgeous moment made all the more sad when we come to the end. The days run away in this life leaving us with a collection of moments like a string of pearls. Cisneros captures this so eloquently, so beautifully.

The book ends with a reflection on where she is now. Cisneros vows to “listen to her night dreams. And so, in her dream she saw all around her were stories…” She realizes “They had been whirling and flying all about her all along…Stories without beginning or end, connecting everything little and large, blazing from the center of the universe into el infinito called the great out there.”

Sandra Cisneros is a truly great American writer. In this era of cynicism and bitterness and anti-immigrant posturing, she brings us back to what is elemental: the need for home; the warmth of memory; the magic of culture. She is a poet in prose, be it fiction or nonfiction, always marching to her own band, celebrating her own, yet universal lyric.

Comments

Post a Comment