Never Passing "Go"

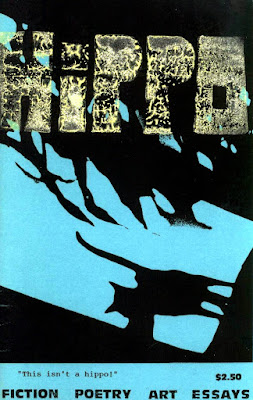

This is an edited version of my story published by Karl Heiss in his magazine, Hippo, in that long ago summer of 1990.

* * * *

Outside the clear glass windows, the headlights of passing cars hurried home in the dark. Inside the crowded restaurant was a swirl of frenetic movement composed of wait staff, busboys, and patrons moving and bumping their way from booth to booth. People at a window table—man, woman, a bond between them that one could see in their eyes—whispered, smiled, chatted. The whole globe of this swirling world existed only for themselves. They stood suddenly, nuzzling each other and moved out of the restaurant together. In contrast, Clara and Josh sat, nearly motionless at a nearby table, he in his standard dark jeans, black tee shirt, and tweed jacket, and she in a simple pink, cotton dress.

“So?” she asked.

“So?” he replied.

The waiter rushed by, sizzling platters resting on both arms. Tangible smells of roasted onion floated above their heads, mingling with the cigarette smoke of the restaurant.

“Do you play Monopoly?” Clara asked.

A five year courtship and he still found cause to wrinkle his eyebrows at her. “Only on rainy days.”

“I always spend my money buying properties. It’s tough because I usually wind up selling them back for cash.” Josh looked around at the other tables, afraid people might have heard Clara’s confession. “How about you?” she asked.

“No, I don’t take chances with my money.”

“It’s only paper.”

A well-known character actor sat in a corner booth. Clara knew he was somebody, but could not remember his name. A woman going to the restroom so intently watched him that she collided with the busboy. Polite apologies were exchanged and both parties kept moving.

“So, can we set a date?” she asked, avoiding his eyes. She feared there might be something too easily seen in his face. She knew this was wrong. He should ask.

“I don’t know.”

She glanced at him but he wasn’t looking at her.

“What about this year at school?” she persisted. “It worked, Josh. We lived together six months and you said yourself it was the best.”

“So?”

“Doesn’t that mean something?”

“Sure,” he answered, meeting her gaze. “It means we saved money!”

Clara couldn’t swallow the choking sensation. “We were good, Josh…” She let her voice trail off. The muscles in her back were corded, tensioned like guitar strings. She kneaded the skin on the back of her neck.

“What do you want me to do?”

“I don’t want anything,” she snapped. “What’s wrong? What changed you? We’ve been over and over this. Nothing was going to stop us. We didn’t need anybody’s blessing. You said,” she choked.

“What?”

“You said you loved me.”

“Yeah, but money, what are we going to do for money?”

“We talked about that too! What happened at that tennis match today?”

“Nothing.”

“What did my father tell you?” She wanted to slam her fork into the wood table. It would stick there, wavering slightly. No one would be able to remove it.

“It was just tennis,” he said. “It was just a game.”

Clara hated tennis. Her father always made her play. Summers, winters, rain, heat, or cold, he would always force her to play. After she had the heat stroke July of her sophomore year at State, the game was over. Daddy still liked tennis, but he never bothered her about playing anymore. Instead, he challenged everyone else—co-workers, acquaintances, her boyfriends. She should have gone with Josh and daddy. She knew her father: big, red-faced man, and how he monopolized the game and the conversation. It was money, finances, stock portfolios. It was college graduations and futures and how much money could be made with certain degrees and occupations. That’s all that ever mattered to her father. Life was a Monopoly game. He had his favorite piece, his favorite moves, and he always avoided unwise or impulsive decisions. Wrong moves must be terminated. Send them to jail. Never let them pass “Go.”

Josh was so open with his brown-grey eyes that changed with his mood. He was boyish and innocent and poetic. The man with two divorces and four daughters sucked him up on a clay tennis court at some country club and spit him out into the net. To her father, Josh was weak. He wanted a money man—a man with substance and meat. A man with these qualities had backing. This was most important: he must have money. Love never mattered. He didn’t want a poet to marry his daughter. Innocent people get slaughtered and poets never play Monopoly.

The waiter levitated in from nowhere and refilled their coffee cups. Clara waited for him to flutter away.

“What did he say to make you change?” she asked.

“Who?”

“My father, you know who!”

“Nothing.”

“He hates marriage,” she spat, “unless he gets something out of it.”

“He has nothing against marriage,” Josh answered. “He said it made him a man.”

“Wrong,” she said. “He’s an asshole and his marriages were disasters, scorched earth.”

“Come on, Clara!”

“No, you come on, Josh! He’s still a manipulator and he got to you.”

Josh let his eyes rove the restaurant. Clara noticed him shaking his head in a silent no. It was a gesture backed by the constant movement of patrons leaving the bistro—walking out into the damp night air. She could smell them, with exotic and varied perfumes as they passed her table. Passing, passing out into the night which in short hours would become day and then night again. The restaurant was nearly empty. The piano player was putting his music away. Glasses with various levels of amber liquids in them decorated the top of the instrument. The piano player turned and sauntered sleepily to the door. Something was ending, had already ended.

“So what are we going to do?” she asked. This time, Clara had no trouble looking at him directly.

“I don’t know,” Josh answered, pushing his plate away. He folded his napkin and dropped it on the table, a gesture of finality. “Too much,” he said to his plate and to her.

“Don’t Josh.” He finally locked eyes with her.

“I’m thinking, Clara. I’m trying to do what’s right. I’m trying to see the future.”

Clara felt the heat build behind her eyes. She felt the moist reflections of early rage seep out the corners of her eye sockets. The flood came and she couldn’t stop it.

“Look, don’t cry,” he said. “I still love you.”

“Oh my God!”

“What?”

“You can’t even come up with an original line.”

The red glow began at his Adam’s apple and flushed upward. “I do. I really do.”

“But it’s just not a sound financial decision right now,” Clara offered sarcastically.

“I just need time,” he said.

“Another cliché!”

Clara slid out of the red booth and walked toward the sign that read “Exit.” People criss-crossed her path—waiters, waitresses carrying platters once hot and steaming but now cold, with scraps of food and refuse. A busboy leaped past, a tray of milky glasses in his arms. Tomorrow, they would be crystal clear again. A woman with a green, silk dress sat at the bar, but even she was moving, rubbing her hand up and down the thigh of the grey, distinguished man standing next to her, gently kissing his neck.

Clara took it all in. She looked down at her own legs. At first, they seemed to move sluggishly, but as she immersed herself in the liquid, flowing movement of the restaurant, she seemed to float. She picked up speed, building momentum for what would come next, for the rest of her life. Then she realized. It was a subtle but powerful difference. She was not propelled by schemes or money or a desire to win. The mass of muscle behind her acceleration was her heart.

Once at the door, Clara gave herself a moment to look back. In the current of movement there was a note of stillness. Josh sat staring down at his fingers spread like a fan on the dark wood table. She remembered when he wrote her poetry and kissed her neck. She remembered when he studied her long fingers, brought her flowers, caressed her. She remembered shared secrets, veiled inferences, and making love on cold, rainy, windy afternoons when they should have been in class but stole a moment to themselves in the connection, the weaving interloping of their bodies. But now, it was only she who prized the jewel of crystal-clear love that once moved between them. Now he would be left behind, holding his Monopoly money and his “Get out of jail free” card, never passing “Go.” She would transcend the game, find love and discover an authentic life. This was the last time that she would ever look back.

Someday he would wake to discover that in the end, the things he valued were ephemeral, that he had missed out by standing still. She would choose another path; she would keep surging forward. In an instant, everything was clear: anything real must move, or die. Clara pushed through the doors out into the night where a warm spring rain had begun to fall.

Comments

Post a Comment