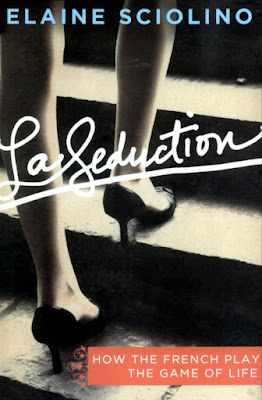

La Seduction

Americans have their stereotypical views of the French, which is why every American should read Elaine Sciolino’s book, La Seduction: How The French Play The Game Of Life (Times Books/Henry Holt and Co., 2011).

Sciolino is the former Paris bureau chief for The New York Times and was once a foreign correspondent for Newsweek. Currently, she lives in Paris with her husband, an American lawyer who practices with a French law firm.

Her goal in the book is to examine the way seduction is an integral component of French culture and behavior. She begins with the custom of the male kissing the hand of a woman to whom he has been introduced. The kiss is not romantic or passionate; it is offered like Americans offer each other their hands in greeting, but it is intimate and unique to French custom. It is all part of the way France integrates the fine art of seduction into every day life.

“In English,” Sciolino writes, “‘seduce’ has a negative and exclusively sexual feel; in French, the meaning is broader. The French use ‘seduce’ where the British and Americans might use ‘charm’ or ‘attract’ or ‘engage’ or ‘entertain’…The term might refer to someone who never fails to persuade others to his point of view. He might be gifted at caressing with words, at drawing people close with a look, at forging alliances with flawless logic.”

France remains an enigma for many Americans. This was never more clear than in the days leading to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, which France opposed. French President Jacques Chirac saw his country’s approval rating in the U.S. fall from 80 percent to 30 percent. “French products were boycotted,” Sciolino writes. “French wine was poured down kitchen sinks. Vacations to France were canceled. French fries became ‘freedom fries’ in the House of Representatives’ cafeteria.” Sciolino characterizes the incident as “the most serious diplomatic crisis between the two countries in nearly a half century.”

In France, philosophers appear on television and enjoy the status of rock stars. The country vigorously embraces a café culture, of thought over action, and the life of the mind is prized far more than physical effort.

Arguably, France has one of the most distinct cultures on the globe. However, some might argue that it is in decline. Sciolino believes this as well. “And yet the French still imbue everything they do with a deep affection for sensuality, subtlety, mystery, and play,” she writes. “Even as their traditional influence in the world shrinks, they soldier on. In every arena of life they are determined to stave off the onslaught of decline and despair. They are devoted to the pursuit of pleasure and the need to be artful, exquisite, witty, and sensuous, all skills in the centuries-old game called seduction.”

Emblematic of the need for seduction in every day life is the palace at Versailles, to which Sciolino devotes a chapter. She calls the wondrous chateau “France’s national monument—to love and to power.” She interviews a gardener there who wrote a book about the palace which included such details as: “the famous actress who loved to visit there to expose herself; the older politician who had sex in the garden with a young woman whom he had tied to a tree; the elderly couple who complained when one of [the] gardeners fell from a tree, landing on them as they were in the throes of lovemaking.”

She devotes a chapter to the magic of the Eiffel Tower, explaining the complex method of repainting the monument every seven years. To complete the job takes sixty tons of paint. The color formula is a state secret, but Sciolino learns that there are subtle differences in shade moving up the tower: light color on the bottom moving to darker tones at the top to create an optical illusion of a uniform look.

What baffles most Americans, however, is the behavior of the French. “For the French,” Sciolino says, “life is rarely about simply reaching the goal. It is about the leisurely art of pursuing it and persuading others to join in.” America is a land of finished projects, of goals realized. At the end of the day, we want to see accomplishment, whereas the French are content to let it ride, especially in appreciation of the journey.

Sciolino believes that as deep as the work ethic is embedded in American culture, the life of the mind is imperative to the French. She writes, “France’s history and literature reflect centuries of crafting ideas and intellectual concepts. The French have long pushed to persuade the rest of the world to consider and even adopt them. Modern philosophy originated in France, with Descartes. The eighteenth-century French philosophes—Voltaire, Montesquieu, Rousseau, Diderot—forged a set of values for society that gave preeminence to reason, democracy, and freedom. In the twentieth century, existentialism bloomed with Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, and Simone de Beauvoir.” France cannot escape its mind-life anymore than America can abandon its obsession with achieving goals and objectives.

Tourists, especially, have differing reactions to the French and their culture. Both men and women in France are expected to please each other on the street—men by verbally complimenting a woman for her beauty, and women by receiving the compliment and enjoying the attention. On American streets, this is tantamount to sexual harassment, the wolf whistle of the working man to the unfortunate beautiful woman pedestrian who happens by the job site. Americans are put off by French behavior. The confusion, says Sciolino, has to do with a smile. “Smiling is complicated in France. Americans are accustomed to smiling at strangers; the French—particularly Parisians—are not. This helps explain why some Americans find Parisians rude.”

By far, the most interesting chapters in the book are the ones devoted to hallmarks of French culture with which the world is so familiar: perfume and cuisine. Sciolino delves into the importance of scent to Parisians especially, giving us a history of the industry. She tells us that perfume has been used in France since Cro-Magnon days, when men rubbed themselves with mint and lemon to remove the taint of body and wild game. In interviews with French perfumers, she finds that Americans value scents of cleanliness and power, meaning deodorant and perfume that can be detected from several feet away. The French, she says, are more subtle and mysterious with their pleasant odors. And food is an orgasmic experience, she writes, full of subtle tastes and textures. The French raise the work of the vine and the labors at the stove to an art form, and tourists should close their eyes and surrender to the experience.

Sciolino also takes us through the gallery of French presidents, explaining how each managed to seduce the world, and where they tripped up in their efforts. Nicholas Sarkozy comes off as one of the worst in history. She brands him as “unskilled as a seducer in the classic French mode.” He is “frank rather than indirect, prone to naked flattery and insults rather than subtle wooing, perpetually in motion rather than taking time for la plaisir. He is contemptuous rather than enamored of the complicated codes of politesse.” He “contracts his words and salts his sentences with rough slang. In a country where food and wine are essential to the national identity, he prefers snack gobbling to meal savoring.”

The book ends with a grand salon dinner party, a fitting finale to a book so connected to good food and seductive culture. In the preparation for the event, we learn that French apartments come with bare kitchens, often with only a water source and maybe a sink. It is custom that the new tenants will install their own fixtures, appliances, and cabinetry. Then there are the rules of etiquette for the dinner party itself. I’ll save a little something for the reader to discover, but let’s just say that the biblical Ten Commandments are positively spare in comparison.

Elaine Sciolino has given us a veritable treat, a meal in itself, in her book. French culture still has much to reveal to the rest of the world, and in an age of global connectedness, it serves us well to be handed such an intricate and intimate study of a country once a super power, but now more of a philosophical influence on the rest of the world. It is not our similarities with the French that should be stressed, but that culture’s uniqueness which should fascinate and intrigue us. France, like a good meal, always surprises, always delights, and Elaine Sciolino prepares a banquet for us, with the depth and nuance of the journalist’s eye on the world.

Comments

Post a Comment