Communion

Jean-Paul Sartre wrote, “The process of writing…includes as a dialectic correlation the process of reading, and these two interdependent acts require two differently active people. The combined efforts of author and reader bring into being the concrete and imaginary object which is the work of the mind. Art exists only for and through other people.”

Jean-Paul Sartre wrote, “The process of writing…includes as a dialectic correlation the process of reading, and these two interdependent acts require two differently active people. The combined efforts of author and reader bring into being the concrete and imaginary object which is the work of the mind. Art exists only for and through other people.”For Sartre, and many other cultural critics, art requires three things: the artist, the object, and the viewer. It is only through the communion of these three that the art is fully realized.

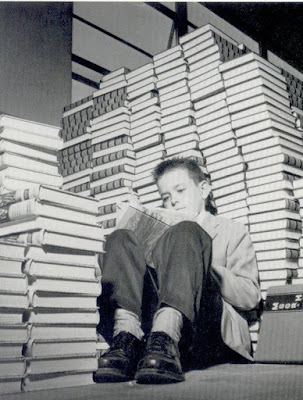

In literature, there are also three conjoined entities: the writer, the book and the reader. Only through the work of these three can the story, the image, the poem be fully imagined and come alive.

Writers write to be read, and anybody who says otherwise is a liar. It is a way for the writer to process the world, to make sense of the experience of existence. Therefore, shut down a writer, refuse to publish him, and he will die. Although it has happened to so many writers and artists, the lowest level of hellacious frustration must be to die before anyone reads the work. We admire Emily Dickinson’s poetry, but no writer wants to be Emily Dickinson. Writers require readers to actualize their work.

Tim O’Brien, in his book The Things They Carried, characterizes the dead as books on a library shelf that no one is reading right now. In a dream, a child version of Tim O’Brien talks to a girl on whom he had a crush, and who subsequently, has died of cancer. He asks her what it is like to be dead. “Well, right now…I’m not dead. But when I am, it’s like…I don’t know, I guess it’s like being inside a book that nobody’s reading.”

“A book?”

“An old one. It’s up on a library shelf, so you’re safe and everything, but the book hasn’t been checked out for a long, long time. All you can do is wait. Just hope somebody’ll pick it up and start reading.”

I think about those lines every time I walk into the library: all those lives, those ideas, those minds, those characters, just waiting for me to pull them down from the dusty shelf and bring them back to life by reading them.

Writers are often asked in those inane interviews or by the patrons who wander into the book store to hear them read, “For whom do you write? Who is your imaginary reader?” As if a writer could conjure a fictional reader alongside his fictional characters! Writers often respond that they write for themselves first, as a way of figuring out what they think.

In truth, it is both ways. We write as a way of making sense of the world, of figuring out our own minds, but we also need to be read. We want readers more than anything else in the world. We crave the communion of minds. A writer without readers is a man without a country.

I think of all the writers I’ve talked with over the years in my reading, often late at night, long after the house has grown silent and ghosts wander freely. Age nine, plowing through one Hardy Boys mystery after another, never realizing that Franklin W. Dixon was the nom de plume of a number of pulp fiction writers. Twelve, and it’s Louis L’Amour, lost in his saga of the Sackett family in the Old West. Brother Ray Bradbury and the creepy carnival, the burning books, and the Illustrated Man. Sylvia Plath, poet and novelist, desperately trying to live while frantically attempting to die. She made me Esther Greenwood. And Frost, and Cummings, and Eliot—oh, we’ve had some great talks! Shakespeare’s kings, Chaucer’s pilgrims, and Huck and Jim floating down the Big Muddy looking for freedom. A dark, stormy night at Wuthering Heights, Pip and his great expectations, the jagged, jiving poetry of Allen Ginsberg, and of course, on the road with Kerouac. Hundreds, thousands of writers whose crude symbols on a piece of pulped up wood led me to visions and hallucinations and adventures. Stories brought to life, Dr. Frankenstein, I presume? Every writer works at the top of the house. The reader brings the lightening.

I love the fragile schizophrenia of reading at night. In the silence, the voices come to me:

“He did not want to be the father of a small blue pyramid.”

“Summer was dead but autumn had not yet been born when the ibis came to the bleeding tree.”

“If a body catch a body coming through the rye.”

“The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.”

“To be great is to be misunderstood.”

“Call me Ishmael.”

“Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil…”

Because your pen and your words go with me.

The voices come fully fleshed out and alive again. On the deck with Horatio Hornblower; sailing across strange seas with the Dawn Treader; with Peter in Neverland; longing for Ithaca with Odysseus; dying on the battlefield with Hektor, in sight of the walls of Troy and home. I have traveled the universe and back, and all my wars are laid away in books, to paraphrase Ms. Dickinson.

Art and literature need us. They are calling from the marbled halls of the museum, across the years from the dusty library shelves. They whisper secrets and promises. They tell us how to live in a world where we are destined to die. They tell us how to be heroes. Listen. Shhh! Listen.

In the quiet communion of writer, book, and reader, the dead and the lost return to tell us stories of love, regret and adventure, and we imagine them to life again and again. The boy and the book and the long dead writer, deep into a winter’s night, traveling.

Comments

Post a Comment