Tell Me The Good News Only

Once, having transferred to my first Catholic high school teaching position, I walked into trouble. I was eager to please and willing to do anything to be successful, an often fatal combination. As I signed my contract, I did not think about the principal’s off-the-cuff remark that, “the tenth grade English teacher is also the faculty advisor for the school newspaper.” I was so excited and overwhelmed planning my classes that I gave little thought to my upcoming foray into journalism.

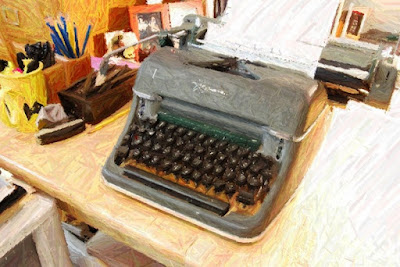

Once, having transferred to my first Catholic high school teaching position, I walked into trouble. I was eager to please and willing to do anything to be successful, an often fatal combination. As I signed my contract, I did not think about the principal’s off-the-cuff remark that, “the tenth grade English teacher is also the faculty advisor for the school newspaper.” I was so excited and overwhelmed planning my classes that I gave little thought to my upcoming foray into journalism.After classes began and I had a free moment, the first task I focused on was setting up the journalism room. Actually, the room was a storage closet, but I was not going to complain. I’d make it work. I carried fifteen electric typewriters up two flights of stairs to our newsroom. I wanted computers, but there were none to spare. “Besides,” the principal assured me, “journalists have been using typewriters for a hundred years. And these are top of the line: they’re electric!”

As I won over my students in my English classes, I started recruiting the best writers for the newspaper. I found out critical information immediately from them. The newspaper was a well-known campus failure. Every new teacher was forced into the advisor position with no budget, no class time, and overwhelming expectations from the administration. “The principal only wants to trumpet the good things at school,” one student explained. “She won’t let you get real stories that make the school look bad.”

The first story we chose to cover began as a rumor. Two of the student reporters heard that a homeless woman had given birth in the park across the street from the school. This was a story that even the local papers did not get. So on a crisp, cold day in November, the two reporters and I headed across the street in the fading twilight to hunt our story.

At the center of the park was an isolated square of grass surrounded on three sides by thick shrubs. It was there that the homeless people camped out. When we arrived, they were cooking their evening meals and preparing for another cold night. One woman who looked to be in her fifties said hello. The reporters opened their notebooks and began to ask the questions we had worked out back at school.

“Yes,” she said, “the story is true, but I’m not lookin’ for trouble.”

“We’re not trying to cause trouble,” one of my new reporters, John, replied. “We just want to know the story.”

“Look, you wait here. I’ll go see Sabine. If she wants to talk to you, she’ll come.

We waited as the woman melted into the shrubbery. It was getting colder and darker. About fifteen minutes later, the woman returned with what I thought was a young man. It was Sabine. She had very short, dark, brown hair and a silly smile. Her work shirt and pants were dirty, and when she sat cross-legged on the grass, her boots had holes in the soles.

“This is her,” the woman said.

It quickly became apparent to us that Sabine was mentally challenged. When asked questions, she giggled shyly. When she did speak, it was in the breathless, high-pitched voice of a child.

“Sabine, these people want to know about your baby.”

“Gone,” Sabine answered, and started to cry.

“Yes,” the older woman said. “The baby’s gone.” She looked at my young students and then at Sabine. “You know, Sabine’s your age. How old are you? Seventeen, eighteen?”

“Sixteen,” John replied.

“I was there when it happened. Someone’s got to tell the story for her because it’s not right. Sabine was pregnant, only no one knew. I knew, but then I can sense those things, just like I knew when it was near her time. I told her to walk to the clinic on Arizona Street, but she waited too long. She didn’t have no baby in the park. If she did, it would have been okay. She tried to walk to the clinic. Got as far as across the street in front of the old folks’ home when the head popped out.”

“Popped out?” John asked.

“From her thing. He private parts. The head popped out. She lay down right there on the sidewalk. One of the nurses from the old folks’ home saw her through the window and called the fire department. The baby came out right there on the sidewalk.”

“What happened?” John asked. “Did they take her to the hospital?”

“Oh yeah, you bet they did. Baby went one way; Sabine went the other.”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“They took her to the hospital, fixed her overnight, and put her back out on the street.”

“What about the baby?” John asked.

“They told her she wasn’t fit to be a mother. They said Child Services would find the baby a good home. And they put her on the street. I found her outside the clinic crying the next day. She still had blood on her shoes.”

“So she has no idea where the baby is?” I asked.

“Nope.”

“Gone,” Sabine sighed as she rocked back and forth with her arms wrapped tightly around her knees.

“What about the father?” John asked.

“What about him?”

“Maybe he could help.”

The woman laughed. “Why don’t you go ask him, kid?”

John stood up. He was angry. “Where is he?”

“Over there.” She gestured across the street to the church.

John was confused. “Where?”

“He lives in the priests’ house. Young guy, blond.”

John and Lawrence looked at me. That sounded like Father Kerry, the school chaplain. Lawrence found his voice. “How do you know he’s the father?”

The older woman shrugged her shoulders. “All I know is, nine months previous, Sabine knocked on that very door and the blond, good-looking priest answered. He gave her food, clothes, that old pair of boots she’s wearing. Next thing I know, she sleeps across the street on the carport roof. Tells me the priest says it’s okay. She tells me he’s nice.”

I was beginning to feel as if I’d fallen down a deep hole.

“He must have known she was pregnant?” Lawrence pushed.

“Sure he did. That’s why he eventually called the cops on her. They kicked her off the roof and told her to stay away from the church.”

I could tell both boys were disturbed. “I can’t believe this,” John mumbled.

“If you don’t believe it, go ask him yourself. He’ll probably tell you Sabine’s the new Virgin Mary or something. All those priests got stories to tell.”

We left the two women in the park and crossed the street. “We can’t let this go,” John said. “A good reporter follows the story. You said that, Mr. Martin. We gotta talk to Father Kerry. He’ll explain what happened.”

I had this sick feeling that I knew how this would turn out. Some time next week, I’d be looking for another job. For sure the article would never see the light of publication, and I’d probably not have to worry about being the journalism moderator. If they kept me, I’d be monitoring after school detention the rest of my time there.

John rang the bell. When the cook answered, he asked for Father Kerry. She told us he was finishing his dinner and would see us in the library. We were escorted into a dark room lined with religious books.

“So men,” Father Kerry said as he entered the room. “You guys are putting in some late hours. School ended a long time ago.” His eyes were cold and steely blue.

“We’re working on the school newspaper,” I replied.

“Father,” John began, “we were just over at the park interviewing for a story. Did you know a homeless woman gave birth over there a while back?”

Something changed in the priest’s face, a slight twitch of the lip. “Yes, I’d heard rumors. Father Roy went over and didn’t find any truth to them.”

“The rumors were true, Father,” Lawrence said. “She really did have a kid in the park.”

“Well, I’ll have to pass that news on to Father Roy.”

John’s voice cracked. “They took away her baby. They said she wasn’t fit to take care of it.”

“She is homeless,” he replied.

John pressed. “They did not even tell her where the baby went.”

“Boys, listen,” he said, leaning forward. “What may seem cruel is really what’s best for both mother and child. What chance would the baby have growing up in a homeless camp in a city park?”

“We were hoping we could find the father,” John said. “Maybe he could help.”

The priest’s face was a mask. “The father is probably another homeless person.”

Lawrence’s voice seemed far away, like the distant rumble of an airplane overhead. “Father, did you let a homeless woman sleep on the roof of the garage last year?”

The priest’s eyes flickered. “Listen, sometimes we break the rules here. We go across the street and give those people money and food. We often make arrangements for them. That’s what priests do. We just don’t work at schools and churches. We help people.”

“The woman says you let her sleep up there for a while,” Lawrence said.

“Well, now that you mention it, I, or maybe Father Roy, we did let a retarded woman sleep up there. She was worried about advances from other men, and we decided she’d be safe up there until we could get her some help. Unfortunately, she became very erratic and we were forced to have her removed by the police.”

“So you know her?” Lawrence asked.

“Yes.” Father Kerry suddenly looked surprised, but his eyes did not change. “Was she the one who had the baby?” Both boys nodded. “Well, it’s a shame that people take advantage of the retarded.” The priest stood up. The interview was clearly over. As we shook hands, the priest stared into my eyes.

Out in the parking lot, the boys talked excitedly. “We should have asked him, point blank, if he was the father,” John said.

“I don’t think he was,” Lawrence replied. “I mean, he’s a priest. He was trying to help someone.”

“What should we do, Mr. Martin?” John asked.

I remembered a line I read in a book about journalism. “You write the facts, the verifiable truth, and let the readers form their own opinions.” It was a simple rule, and the only thing I could think of to say.

The boys took off for home. Tomorrow, they would write their story, and the facts alone should make things bad enough. I slumped against my car. It was a chilly night with rain predicted for the weekend. I was so exhausted that for a moment, I seriously considered resigning on the spot.

The principal, a nun, came across the parking lot from the convent on her way to evening Mass. “Hello, Mr. Martin,” she said. “What were John and Lawrence so excited about?”

“A newspaper story they’re writing for our first edition. A homeless woman had a baby in the park.”

“Oh,” she said. “Well, good night, Mr. Martin, see you tomorrow.”

“Good night, Sister,” I replied. She started on in the dark toward the softly lit church, but stopped suddenly and turned around.

“Oh, Mr. Martin?”

“Yes?”

“She wasn’t one of our graduates, was she?”

It was at that moment that I knew the school paper would never be published. By the next fall, I was gone, and a new teacher struggled with the cursed burden of finding only the good news to tell the world.

Comments

Post a Comment