Taking Notes

The bank that owns the property next door to me is preparing to sell it. So yesterday, the entire contents of the former occupants’ lives were dumped on the sidewalk for everyone to pick through and take away. I walked over to see what the hullabaloo was all about and found a first edition cloth bound copy of William Manchester’s Goodbye, Darkness. I stood there for a moment in the gathering twilight thinking what were the chances that I would find that book—one I reviewed a while back, and written by my current obsession, the historian Manchester—in the midst of all the rubble.

The bank that owns the property next door to me is preparing to sell it. So yesterday, the entire contents of the former occupants’ lives were dumped on the sidewalk for everyone to pick through and take away. I walked over to see what the hullabaloo was all about and found a first edition cloth bound copy of William Manchester’s Goodbye, Darkness. I stood there for a moment in the gathering twilight thinking what were the chances that I would find that book—one I reviewed a while back, and written by my current obsession, the historian Manchester—in the midst of all the rubble.As I continued looking through the junk, I found a box of notebooks. “Northwestern” was embossed on the covers. Someone had written “Microbiology” underneath the college logo in black marker. There were maybe ten notebooks in all. I took one up and began paging through it. There, in the neatest handwriting I had ever seen, were someone’s notes for her study. Things were labeled, diagrammed, cross-referenced. Chapters were delineated, outlined, organized. I could write a book with those notes, maybe several books.

And so I was thinking of note-taking.

I have become a compulsive note-taker. I took notes in school, like any student, but the notebooks I kept were messy, revealing someone who had yet to decide what his handwriting would look like, or if he would eschew handwriting altogether and be a printer, like his father. There were notes in cursive following the best my Catholic school teachers could do. Other pages were mere scrawls—disorganized, unclear, containing huge gaps when I probably tuned out in class.

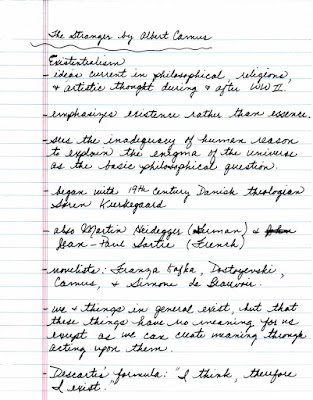

After I became a teacher, my handwriting and my note-taking skills improved. My biggest problem was my left-hand writing: I suffered tremendous writer’s cramp if I had to write more than a page continuously. Years ago, I taught myself to type, and I have always found myself a quicker typist than a handwritten note-taker. I have settled on a procedure that works well for me. I write notes in handwriting in either a reporter’s notebook, or a Moleskin notebook. The notes tend to be bullet points, short, brief ideas or lines, sometimes quotes. Later I transcribe them to the computer when time allows. Typed or rewritten on legal pads, I gather the pages in file folders and place them in a cabinet near my desk. This is how I build my teaching and writing.

Notes to me are everything. Which was why I was so sad to find those notebooks. A whole study, it would seem, regarded as trash.

My students take notes as I teach, and I often ask them what they are noting. I am interested in how they process the information, how they determine what to note and what to leave out. For the younger classes, I am responsible to teach them how to note. I tell them not to try to write down everything the teacher says, especially if the material is covered in a textbook or set of readings. Teachers come in two flavors, many times: the one that lectures strictly by the book, and the other that uses the book as a jumping off point for additional learning. If the teacher sticks to material in the book, the student has two opportunities to note. If something is missed in the lecture or discussion, then by reading the chapter or section, the missing pieces can be filled in. If the teacher uses the text as a beginning, then taking notes during the class is a necessity, and to miss the readings and the lectures is to miss two different things.

In high school today, I think the move is away from lecture and more toward cooperative learning, group projects, presentations, seminar approaches. I see my students glaze over when the lecture goes on too long, however, the Socratic method is my best tool. It takes patience and resilience to keep hammering at them with questions to lead them to the answers, but if I do it right the entire class is involved. On my less perfect days, I wind up cutting corners and giving away the answers, not the best way to teach. Student involvement is key.

For me, one guide when teaching is to remember how I learned. Even now, how do I learn new material? The most important difference between me as a student and me as a teacher is that the teacher wants to learn, has questions he wants answered, and loves to research. Not so the student of yester-year. My students are being put through the paces, as I was at their age. Therefore, the questions are the teacher’s not the students’. The trick is to get the students to want to know, to ask the questions. The questions are far more important than the answers.

So notes, highlighting and annotating texts, how do we sort it all out? Some is intuitive. You can feel when something is important. Maybe the teacher repeats it several times, or it comes up repeatedly in the material. When I read, the sentence seems to jump out at me, especially when reading history or science. Literature is a bit trickier. There, repeated readings are a must. I cannot figure out where a poem or chapter or short story is going until I have read it through once. Then I can work through it again and find what is important. Literature calls for repeated readings.

All in all, note-taking is a personal skill; students must find a system that works best for them. That is another reason why I found those notebooks, left in the cold and darkness at the curb, so sad, indeed. They are the product of someone’s thinking, considering, living with a subject. They are a record of what that person found interesting, and placed enough value in that time was spent gathering the information. Sure, it could have been just a class, but it was learning, nonetheless, and an indication of a mind-life. Now, in the midst of widespread foreclosures and a difficult economy, the notebooks are rubbish.

Comments

Post a Comment